Pricklies of North Cacti-lacky

North Carolina is home to wide variety of plants, some of which are native or commonly seen on the Ocracoke. We’re all probably accustomed to seeing the brightly colored Joe-Bells, various asters, honeysuckle, and wild roses which thrive in the coastal environment. But don’t let those bright blooming wildflowers distract you. Off the beaten path, one may wander into unforeseen treacherous areas. Cacti flourish along North Carolina’s coastal plain and barrier islands, and you can spot them along sand dunes as well as in areas with thick vegetation. I’ve been fortunate enough to avoid injury by these plants, but I’ve heard personal accounts of how awful they are.

The Outer Banks is home to a couple types of “Prickly Pears.” One type, the Dwarf Prickly Pear, grows brightly colored blooms and does best in areas that have prolonged exposure to the sun. The blooms begin appearing in spring and the prickly clusters can produce hundreds of flowers. By fall these flowers will turn into a brilliant red “pear,” – gardeners can plant them in pots or in large flowerbeds in order to harvest the fruit. These cacti tend to grow up and out, rather than across that ground, and streeettttch to reach the sunshine, causing the pads to become quite large. Some pads, from chasing the sun, can stretch to be three-feet in diameter! I’ve seen many of these plants in and around Avon, and last May, I noticed bunches of them along the side streets, their bright yellow flowers beginning to bloom.

Here on Ocracoke you’re likely to encounter the Cocklebur Prickly Pear. These deep purple and green cacti grow across the ground, are shaped like potatoes, and can be unnoticed until someone (maybe even you) steps on the plant. Their large needles are inches long and quite sturdy. They come out of the parent plant remarkably easy, but it isn’t so easy to remove them from your skin. And there’s a good chance you’ll be left with teeny-tiny needles inside the wound, which can lead to infection.

This very thing happened to Ocracoke resident Bob Kremser. He was out at the National Park campground helping some children search for a ball that went rogue and to see if the plants needed to be cleared for the safety of visitors. Having spotted a cocklebur prickly pear he sidestepped it, being sure to walk clear of the plant. Little did he know these things have booby-trapped themselves. When he placed his foot on the ground, he somehow triggered this booby-trap and one of the clusters flung itself towards Bob. He ended up with a barb in his skin, which he removed. Later, the wound became infected and he had to be placed on an antibiotic.

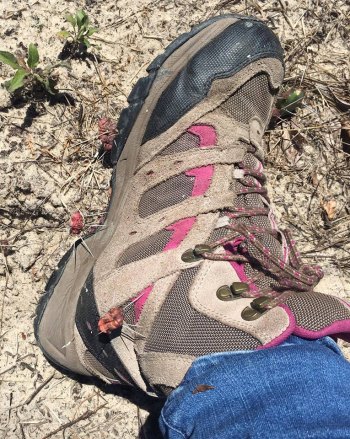

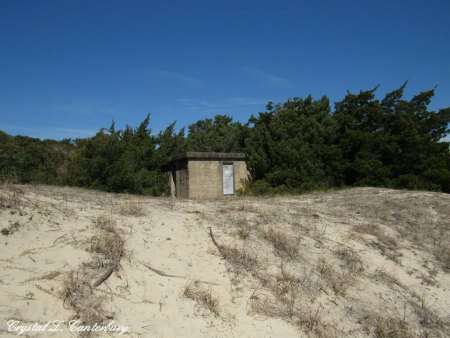

As a general rule of thumb, whenever I plan to go off the beaten path, I wear hiking boots or hiking shoes. The sand spurs alone make me think twice about wearing tennis shoes or sandals, but these cacti are definitely a good reason to wear heavy-duty foot attire. Recently, I explored Loop Shack Hill, where the Navy Beach Jumpers trained during the Second World War. Having on my hiking boots I felt quite confident that I needn’t worry about injuring my feet. As I scaled the sand dune terrain, my focus was on locating the old base. When I spotted the buildings I paused to take photos; that’s when I noticed my boots were covered in barbs and small bits of cocklebur prickly pears.

Fortunately I couldn’t feel a thing, but it was no easy feat removing them from the sides and bottoms of my boots. One of the dunes by an old building was covered by these prickly pears. Being that I thoroughly enjoy capturing Ocracoke in photographs, I attempted to take a photo to show the vast amount of these plants. Lying on the ground was not an option, so I decided to squat down. I quickly realized that one bad move or even a gust of wind could knock me off balance, which would have either landed my bum on some of the barbs or I’d fall over onto my hands and knees. Neither of those outcomes seemed especially fun, so I remained standing. The photos I took in no way do the landscape justice. After all, the plants look like harmless little dots. It’s only upon close inspection that one is able to appreciate what the barbs can do.

When I made way back to my car, I was careful to avoid stepping on any of the plants. Thinking I’d managed not to collect any, I sat down in the driver’s seat. That’s when I felt a scraping on my jeans and realized I had in fact not outsmarted Mother Nature. I gently got out of my car and began dragging my feet on the ground. Quickly I realized that leaving these barbs near the Navy Beach Jumpers memorial wasn’t the best idea, as people frequent the site, so I carefully picked up the removed barbs, walked to the dune line, dropped them there, and continued dragging my feet. To the people driving by, I must’ve looked like I was scraping off some heavy-duty dog poo!

Happy (and safe!) exploring!

Who, you may ask, were the Navy Beach Jumpers?

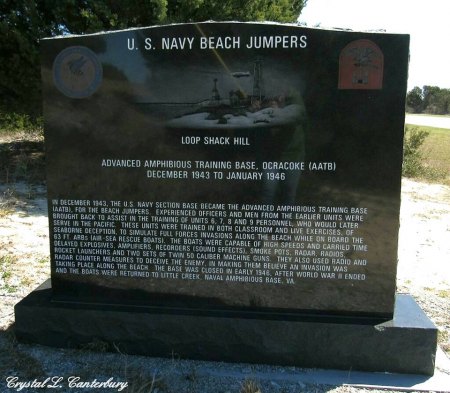

On the southbound side of Highway 12 is a marker dedicated to the Navy Beach Jumpers who trained here during World War II. American actor Douglas Fairbanks joined the U.S. Navy when the U.S. entered the war, and was stationed in England on a special assignment. While there he learned of how the British set up and performed fake invasions in an effort to get the Germans to move their equipment to another location. Once their goal to get the Germans to relocate had been achieved, the British would invade at another unoccupied area.

Lt. Fairbanks returned to the States and proposed training sailors to become beach jumpers in an effort to accomplish the same thing as the British. Admiral H.K. Hewitt, then Commander of Amphibious Forces and all U.S. Naval Forces in Northwest African waters and the Western Mediterranean, organized and acted on Lt. Fairbanks’ proposal.

Beginning in the winter of 1943 into 1944, 180 officers and 300 enlisted men were organized and sent to Ocracoke Island to begin training. While the base was in operation, no one was allowed on Ocracoke’s beaches or near the base. To create the illusion of battle, the men in training would play recorded sounds of war through loud speakers placed on the decks of P.T. boats, launch fire crackers and use smoke pots to replicate battle scenes, and tin foil covered balloons were used to cause communications interference. After successfully learning the maneuvers, the “tactical cover and deception units” – as they are called on the Navy Beach Jumper Association website – were sent to Pacific battlefronts.

The Beach Jumpers were active from 1943-1946, and again from 1951-1972, playing a part in both World War II and the Vietnam War.