War Along Ocracoke's Shores

As an employee at Ocracoke’s Visitor Center, I hear a lot of the same exclamations and am asked similar questions each day. “How do we get to the lighthouse?” “Was Blackbeard really killed here?” “Oh my gosh! I had no idea the Germans got this close!” It’s pretty interesting that so many significant historical events took place on or near this tiny island, and some of the most surprising and unknown events are retold and absorbed within this tiny building.

On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and his wife Sophie were assassinated by a Serbian national. Tensions between the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Serbian government had been increasing and came to a head because of the assassinations. Exactly one month later, Emperor Franz Joseph, head the Austro-Hungarian Empire, declared war on Serbia, beginning what became known as The Great War. Over the next several weeks Germany joined the Austro-Hungarian effort and declared war on Russia, France, and Belgium. Shortly thereafter Great Britain declared war on Germany.

The United States, while aware of the conflict in Europe, remained neutral and even maintained trade with Germany. In February of 1915, Germany formed a blockade of Great Britain with their U-boats and indiscriminately torpedoed vessels, considering each a legitimate target. The United States government became increasingly angry with Germany’s actions as they were destroying merchant ships along with European war ships. When a U-boat sank the passenger vessel Lusitania on May 7, 1914, killing 1,198 civilians, 128 of which were American, the U.S. government was outraged. In response to the outrage from the United States, Germany said it would no longer sink ships before announcing the intention, but the opposite happened. In April of 1916, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson warned Germany to cease its no-holds-barred submarine warfare tactics. He was re-elected President on November 7, 1916 and campaigned under the slogan “He Kept Us Out of the War”.

In the early part of 1917, the United Stated grew more and more outspoken about the government’s distaste of Germany’s maritime war tactics, yet remained uninvolved with the war. Then, Great Britain intercepted a telegram from Germany to Mexico. Called the “Zimmerman telegram”, in it Germany promised Mexico territory within the United States if Mexico aligned itself with German war efforts. This was the final straw for President Wilson, so on April 2, 1917, he asked Congress for a formal declaration of war. On April 6, 1917 the United States declared war on Germany.

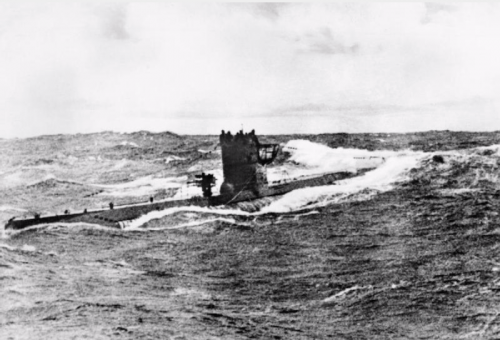

In the following months the United States mobilized and sent troops to Europe. But the German threat to the U.S. had not diminished. U-boats continued patrolling the East Coast, sinking ships and causing skirmishes.

The Light Vessel Diamond Shoal, which operated as part of the United States Lighthouse Service (U.S.L.H.S.), patrolled the waters around Hatteras Island beginning in 1898. She was originally intended to patrol in the Delaware Bay, but remained stationed in North Carolina for twenty years. When the United States entered World War I in April of 1917, Light Vessel Diamond Shoal (LV-71) continued patrolling the coast as she had been doing previously. On August 6, 1918, LV-71 found the stranded American cargo ship SS Merak, which had been attacked by U-140 as it made the voyage from New York to the West Indies. The Merak successfully evaded the initial torpedo strike, but ran aground. U-140 surfaced and began assaulting the stranded vessel with its deck gun. The crew of the Merak escaped unharmed and the men were soon picked up by Light Ship Diamond Shoal. LV-71’s Master, Walter Barnett, sent out an alert to other ships of the U-boat’s presence. As a result, U-140 returned to the scene and destroyed what was left of the Merak. The Germans also destroyed Light Vessel Diamond Shoal after allowing her crew and the rescued crew of the Merak a safe trip to land on one of LV-71’s lifeboats.

One of the most incredible and famous rescues occurred almost a week later when the SS Mirlo, a British oil tanker, was torpedoed off the Outer Banks . The attack happened on August 16, 1918, near the present-day village of Rodanthe. The SS Mirlo was split in half by the torpedo, and instantly its gasoline and cargo of oil ignited, covering the surrounding water with fire. The fire was visible for miles, and the crew of the Chicamacomico Lifesaving Station, having seen the flames, jumped in to action. As they launched out into the surf through the rough breakers, the heat coming from the fire could be described as an inferno. The over six hour rescue was accomplished through walls of fire so hot it singed the hair of the crewmen, smoked their cork life vests, and blistered the paint on their boat. The Lifesaving crew was able to save 42 of the 51 British sailors. The nine sailors who did not survive drowned when their lifeboat capsized.

The SS Merak, Light Ship Diamond Shoal, and SS Mirlo were three of the ten ships sunk by German U-boats off the North Carolina coast during World War I.

After the Treaty of Versailles was signed on November 11, 1918, ending War World I on the Western front, Europe began to rebuild. Over the next decade, however, there was still unrest within Europe, and, beginning in the early 1930’s, tensions began coming to the forefront.

European and Asian nations waged brutal attacks on their neighboring countries and even their own citizens. Dictators seized power, murdering anyone they felt was a threat. Rights were taken away from Jews and non-Aryan citizens within Germany. Policies put in place as a result of the Treaty of Versailles were violated by German leader Adolph Hitler, angering the Allied countries. In 1939, war broke out across the European continent, causing mass casualties, rationing, and violent air raids which lasted for the next several years. War continued, spreading through parts of Africa and the Middle East, as well as in the Pacific. During this time, the United States remained neutral and didn’t get directly involved in the war.

Towards the end of 1940, the Lend-Lease Act was proposed. When it passed in March of 1941, the Act allowed the U.S. to begin providing military aid to foreign nations fighting the war. Congress appropriated the money to “the government of any country whose defense the President deems vital to the defense of the United States.” The implementation of the Lend-Lease Act was one step closure the United States became to joining the war.

On December 7, 1941, Japanese fighter pilots attacked the United States Navy base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, forcing the U.S. and Great Britain to declare war on Japan the next day. On December 11, 1941, Germany declared war on the United States, thrusting the country into the conflict in Europe.

As a result of the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy was left almost destroyed, leaving the U.S. ill-equipped to protect itself from the aggressive Germans. Beginning in January of 1942, Germany launched a U-boat offensive in the Atlantic Ocean along the East Coast of the United States. Many of the vessels torpedoed by the U-boats were carrying U.S. supplies en route to Europe as part of the Lend-Lease Act. Because of the torpedo strikes, the villages along the Outer Banks went completely dark at night, making it harder for the Germans to navigate the waters off present-day Cape Hatteras National Seashore. When torpedo strikes occurred, they were described to sound like great booms of thunder, sometimes rattling walls and windows, and even cracking the walls of a few homes.

Off shore, water would light up as gasoline and oil from the damaged vessels burned, and oil slicks cloaked the beaches in the following days. In all, it is estimated 150 million gallons of oil spilled into the ocean and onto the beaches during 1942, and it is believed these attacks were intentionally kept from the news by the U.S. government in an effort to prevent widespread panic. One of these attacks struck close to Ocracoke. Caribsea, a U.S. merchant vessel, was torpedoed by a U-boat on March 11, 1942. On board was James Baum Gaskill, an Ocracoke native. Several days after the attack, a nameplate from the vessel washed onto an Ocracoke beach, indicating the vessel had been destroyed. It wasn’t until several weeks later an official statement was released about the attack, though Gaskill’s family knew his fate once word had spread of the nameplate’s discovery. Now, a cross carved from the spar of wood attached to the nameplate can be seen in the sanctuary of Ocracoke’s United Methodist Church.

During 1942, the U.S. borrowed twenty-four manned British trawlers to serve as patrol boats and escorts for tankers and vessels carrying supplies up and down the coast. The trawlers were converted into anti-submarine vessels, armed with weapons and artillery, and conducted regular outings looking for German U-boats. One of these converted trawlers was HMT Bedfordshire. Built as a commercial fishing boat, Bedfordshire was completed and launched in August of 1935. After World War II began, the British Royal Navy began acquiring non-wartime vessels for use as anti-submarine vessels. The Royal Navy acquired the Bedfordshire in August of 1939 and quickly began converting her into an armed naval trawler, complete with a four-inch gun, machine guns, and depth charges.

A United States Navy Base was established on Ocracoke in the spring of 1942 and was used in part to conduct beach patrols, mine sweeps, and defend against German U-boats. During this time period, the United States Coast Guard tamed a small herd of wild Banker ponies to help conduct lengthy beach patrols and aid in look-out efforts up and down the islands. In Hatteras Inlet, in an effort to protect allied vessels, a minefield was created, but after five accidents and overwhelming amounts of upkeep, the operation was suspended.

Beginning in March of 1942, the twenty-four converted trawlers began assisting the United States with the anti-submarine efforts along the East Coast. HMT Bedfordshire operated out of Morehead City and primarily patrolled the waters around present-day Cape Lookout National Seashore. On April 18, 1942, the crew of HMT Bedfordshire helped the U.S. Navy search for wreckage of U-85, the first U-boat sunk by the U.S. Navy. They also stood guard during salvage efforts, which were eventually stopped four days later. The rest of the month was spent patrolling around Currituck Island, Hatteras Island, and Lookout Shoals.

In the early part of May, HMT Bedfordshire conducted more salvage and rescue missions. On May 10, 1942, reports of a U-boat sighting were issued. HMT Bedfordshire and HMT St. Loman, another converted trawler, were dispatched to look for the U-boat. In the early hours of May 11, U-558, believing the British trawlers had found them, fired several torpedoes. HMT St. Loman was able to maneuver and evade being struck. HMT Bedfordshire was soon fired upon twice. The second torpedo struck the vessel, causing it to sink almost immediately.

On May 14, two bodies were discovered by Coast Guardsmen, having been washed onto Ocracoke Island. The uniforms were identified as those belonging to the British Royal Navy, and the bodies were soon identified as Sub-lieutenant Thomas Cunningham and Ordinary Telegraphist Stanley Craig. They were buried in a small plot of land next to a local family cemetery in Ocracoke village. A few days later two more bodies were discovered. Though never identified, it was presumed they were sailors on HMT Bedfordshire. They were buried alongside Cunningham and Craig. A fifth body washed up onto Hatteras Island and was discovered on May 21. He was buried next to a British merchant sailor believed to be from the San Delfino, which had been struck in a torpedo attack the previous year.

By July of 1942, German U-boats had sunk 397 vessels and killed over 5,000 people, with the majority of those strikes occurring around Cape Hatteras. Because of the numerous attacks, the waters off the North Carolina coast earned the name “Torpedo Junction.”

A couple years later, Ocracoke once again became a site for naval operations. In 1944, the navy base was converted into an Amphibious Training Base, where the U.S. Navy Beach Jumpers were trained. This organization, trained as a tactical cover and deception unit, later became the Navy SEALS. In 1945 the purpose of the compound changed again, this time being used as a Combat Information Center, but closed permanently in 1946.

If you visit Ocracoke village, you will be able to see a large white cistern located on the lawn of Ocracoke’s National Park Service Visitor Center, which is all that’s left of the U.S. Navy Base from World War II. The small plot of land where four British sailors were buried in 1942 still remains and is currently maintained by United States Coast Guard. Each year members of the community, visitors, and members of the U.S. Armed Forces, plus Officers from foreign militaries gather at the British Cemetery to commemorate the lives of the sailors and sinking of HMT Bedfordshire.

*For more details about the events leading up to, during, and after World War I and World War II (there are so many more than what I mentioned), visit www.pbs.org. By typing “WWI Timeline” or “WWII Timeline” you will see a series of links that will direct you to pages of events detailed in timeline format.