The Story of the HMT Bedfordshire

All are welcome to attend the graveside ceremony followed by a luncheon at the Ocracoke Community Center.

To prepare for the ceremony, read this article from the Ocracoke Current archives (May, 2015):

In 1987 my family moved from England to Maryland, and in 1989 – with advice from one of my dad’s coworkers – we came to the Outer Banks for the first time. We stayed in Rodanthe for a few years, and then primarily vacationed in Avon. The man who recommended the Outer Banks as a destination said we absolutely had to get on the ferry and go to Ocracoke, and my parents, being adventurous and fun people, decided we should go. I was a seven-year-old kid when we first came to the Outer Banks, so I don’t remember immediately falling in love with place, but according to my parents, I did.

Each year we vacationed I grew more and fond of the Outer Banks, especially Ocracoke Island. Twice we stayed for a week on Ocracoke; once at Blackbeard’s Lodge, another in a rental cottage, but made day-trips to Ocracoke from Hatteras Island each year. I really wasn’t interested in anything outside of being on the scenic unspoiled beaches or doing “touristy” stuff in the village. Even the vast salt marshes, wetlands, maritime forests, and wildlife didn’t catch my attention. I also couldn’t be bothered with things such as history since, as a teenager, I already knew it all, as teenagers do. I regretfully ignored the unique and rich history of Hatteras Island, Ocracoke Island, and Portsmouth Island. I clearly remember my dad trying to get me to pay attention to the British Cemetery on Ocracoke, for example, so we’d go, but I never really had much interest.

When I moved to Ocracoke in August of 2010, something finally sunk in: The British Cemetery holds the remains of four Royal Navy sailors and is a memorial for the Royal Navy sailors who were never found. Their vessel? HMT Bedfordshire. I was born in Bedfordshire, England. Their vessel, along with many others, was torpedoed and sunk during World War II by German U-boats. HMT Bedfordshire is my one connection – random as it may be – to Ocracoke.

Just a quick side note: Once we moved to Maryland and I started at the local elementary school, I was called a “pirate” by the other Kindergarteners in my class. I had an English accent and a patch over my right eye in an effort to correct my left, so looking back I’m sure I did appear and sound a little like a pirate. Blackbeard… my five-year-old “pirate” self? I see a connection… I think, even if I’m stretching it a bit.

In the wake of the devastating Japanese attack on the United States Navy at Pearl Harbor, the U.S. was left profoundly ill-equipped and unprepared to protect the East Coast, where German U-boats were known to be located. Numerous merchant ships were torpedoed by the Germans along the United States' Atlantic Coast, thus earning the waters off North Carolina the name "Torpedo Junction." British Prime Minister Winston Churchill sent vessels belonging to and members of the Royal Navy over to patrol and help protect the East Coast of the U.S. This endeavor allowed many vessels – carrying fuel and military supplies for the Allied cause, plus other cargo – safe travels and prevented the deaths of more merchant seamen.

HMT Bedfordshire was completed in August of 1935, and functioned as a commercial fishing trawler for the next four years. In August of 1939, the Admiralty – the organization responsible for commanding the British Royal Navy – acquired the trawler and turned it into an anti-submarine vessel. Germany declared war on the United States on December 11, 1941, and by the end of January 1942, German U-boats had sunk 35 Allied Vessels off the American East Coast.

In March of 1942, the Royal Navy sent 24 armed trawlers to the East Coast to aide the U.S. Navy in their anti-submarine efforts. Beginning in April 1942, HMT Bedfordshire – along with several other Royal Navy vessels – was stationed in Morehead City, NC. These trawlers, which had all been converted into armed anti-submarine vessels, began patrolling the waters off North Carolina for German U-boats, torpedo attack survivors, and wreckage. Their search and rescue missions were conducted mainly along the present-day Cape Hatteras National Seashore and Cape Lookout National Seashore.

One of these missions began on April 18, 1942. The U.S. Navy sunk U-85 near the shores of the Bodie Island Lighthouse, and it was the first U-boat sunk by the U.S. Navy off the East Coast. HMT Bedfordshire stood guard for the next four days while the U.S. Navy attempted to salvage the U-boat, but the attempts proved unsuccessful. On April 22, 1942, the Bedfordshire left the location and went on to spend the remainder of April patrolling the present-day Cape Hatteras National Seashore and Cape Lookout National Seashore. On May 10, 1942, HMT Bedfordshire and HMT St. Loman were on patrol searching for a U-boat, which was reportedly in the vicinity of Ocracoke Island. U-558, fearing they'd been located, began firing at the St. Loman; luckily the trawler evaded the torpedoes. On May 11, U-558 fired two torpedoes at the Bedfordshire, the second of which struck the vessel and caused it to sink almost immediately. All 37 Royal Navy sailors were lost.

On May 14, 1942, bodies of two sailors from HMT Bedfordshire washed onto Ocracoke's shore. Sub-Lieutenant Thomas Cunningham, 27, was identified by Ocracoke Naval Investigator Aycock Brown. Ordinary Telegraphist Stanley Craig, 24, was also identified. Weeks before his death, Sub-Lieutenant Cunningham had given Brown six British flags to drape over the coffins of several Royal Navy sailors who had been killed in torpedo strikes. Brown placed the remaining flags over the caskets of Cunningham and Craig.

Later in the afternoon of May 14, island residents buried the two sailors in plots in Ocracoke Village, next to a small family cemetery. In the days following, the remains of two more sailors were discovered, and though never identified by name, were identified as sailors from HMT Bedfordshire. They were buried alongside their fellow crewmen. A fifth body from the Bedfordshire washed onto the shore of Hatteras Island and was buried near the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse. His grave is next to one of a British sailor from the San Delfino, a merchant vessel that had been torpedoed in 1941.

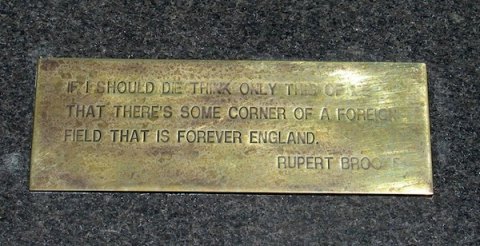

Crosses made for the U.S. Navy in 1942 marked the gravesites of the four sailors. For the next forty-one years the crosses remained, then were replaced with regulation British markers from the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in 1983. That year David Esham, who was President of Ocracoke Preservation Society, was able to save the crosses from being destroyed and kept them stored under the Pony Island Motel. The crosses were eventually moved to the Ocracoke Preservation Society building for storage, and in May of 2001, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission granted permission so the crosses could be displayed at the cemetery. The black granite memorial, which is displayed with the four crosses, was donated by the people of Ocracoke in 2005 to commemorate the sailors of HMT Bedfordshire.

Each year, on the Friday closest to the anniversary of HMT Bedfordshire's sinking, members from the United States National Park Service, United States Coast Guard, and British Royal Navy join with residents and island visitors to commemorate the British seamen buried on Ocracoke Island. The names of the deceased are read aloud, which is then followed by the playing of "The Last Post." Wreaths are placed on the markers and memorial, and a 21-gun salute concludes the memorial service each year.

A War Graves Committee, made up of representatives from the U.S. Coast Guard, the Coast Guard Auxiliary, the Royal Canadian Navy, the Graveyard of Atlantic Museum and their Friends of the Museum organization, and a representative from Ocracoke organize the events. The Ocracoke ceremony and luncheon is sponsored by Ocracoke Civic and Business Association and paid for with occupancy tax funds and private donations.

The British cemeteries located on Ocracoke and Hatteras Islands are the only two foreign cemeteries on U.S. soil.

Note: Trawlers, whether converted into naval trawlers – as the Bedforshire was – or orginally built as naval trawlers, were given the HMT prefix by the Admiralty of the British Royal Navy. HMT is the abbreviation for His Majesty's Trawler. The prefix HMS, His Majesty's Ship, can also be used as a prefix for Royal Navy armed trawlers.

Thomas Cunningham was a Sub-Lieutenant at the time of his death, but was buried as Lieutenant Thomas Cunningham, after being posthumously promoted.