WWI Along the NC Coast

Michael Lowrey, associate editor of Carolina Journal and main contributor to uboat.net, came to Ocracoke for a public session to discuss the German U-boat campaign that occurred off the North Carolina coast during World War I. The National Park Service’s Outer Banks Group hosted the event at Ocracoke’s Community Center, January 12, 2015. Another was held in Buxton on January 13.

June 2014 marked the 100th year since World War One, the Great War as it was called, began. On June 28, 1914 a Serbian nationalist assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophie – both of the Austro-Hungarian Empire – which increased already existing tensions between the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Serbian government. Germany very quietly announced its allegiance to the Austro-Hungarian Empire on July 5; shortly after war was declared. As was expected, Russia backed the Serbian government; Great Britain, France, and Belgium soon sided with Russia and Serbia, creating the Allied Forces (Italy and Japan also joined the Allied Powers). On July 28, 1914, the Central Powers (Germany, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Ottoman Empire) declared war on the Allied Powers. Between 1914 and 1917 the Unites States remained neutral, continuing trade with Great Britain and Germany.

World War I was a devastating conflict, causing about 16 million civilian and military deaths, with about 21 million wounded. Advancements in large machinery, weaponry, and war tactics lead to the violence and slaughter that lasted four years. Trench war-fare, tanks, machine guns, large war ships, mines, poison gas, and U-boats all contributed to the carnage. It’s hard to imagine the war reaching the United States, as we mainly see photos and read or listen to accounts of the war on the European continent. But, briefly, German U-boats made their presence known, appearing on the United States’ east coast for various reasons.

Beginning in 1914 and lasting through 1918, German U-boats proved to be successful war machines. Mr. Lowrey referred to this time as the “U-boat War” years. Still, the Imperial German Navy (also referred to as the Imperial Navy) remained inferior to Great Britain’s. The Royal Navy, at the time, was the largest and most powerful in the world, and in February 1915 formed large-scale blockades. The Blockades - which protected the North Sea and English Channel, down through the Atlantic Ocean, the Baltic Sea, the Bay of Biscay, and the Mediterranean Sea – were formed to prevent the Germans from not only accessing or cutting off the Allied Powers, but also to prevent them from receiving and shipping their own supplies and goods. The Royal Navy’s blockades were successful. The U.S. still had a trade agreement with Germany at this time, and because of the blockade many merchant ships were turned back or had to go through rigorous inspection by the Royal Navy. The Imperial Navy had previously only sunk armed wartime vessels, allowing merchant vessels and passenger boats safe passage, but their wartime actions were about to become more vicious as the blockades proved to be a successful tactic. The German government blamed the Royal Navy for the deaths of 424, 000 of its civilians due to starvation and disease (from 1914 through December of 1918), and the Imperial Navy began waging a fierce naval war, using tactics with no regard for international law.

Leading up to 1915, several American merchant vessels were sunk, and in February 1915, Germany announced its intent to sink any vessel that entered into the warzone, neutral or otherwise (this statement and subsequent actions went against international law, and enraged the Allied Powers). In March of 1915, a German cruiser sank a private American vessel, William P. Frye. President Woodrow Wilson was furious, and the German government issued an apology, saying the attack was an “unfortunate mistake.” This apology, however, did not hold. On May 7, the British-owned ocean-liner RMS Lusitania, which was carrying passengers and munitions from New York to Liverpool, was torpedoed and sunk by a U-boat. There were nearly 2,000 people were onboard of which 1,201, including 123 Americans, were killed. Following the attacks on American merchant vessels, the sinking of RMS Lusitania, and Germany’s wartime statement, the neutral attitude the majority of Americans previously had toward Germany at the outbreak of World War I began to shift.

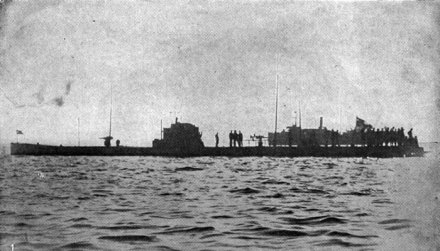

In 1916 a German U-boat made an appearance in the United States. At the time the United States still had an agreement with Germany, trading tin and rubber for nickel. To continue trade and in order to evade the Royal Navy, Germany built large merchant U-boats. After successfully avoiding detection by the Royal Navy in the English Channel, U-boat Deutschland surfaced in Baltimore, Maryland on July 7, 1916. A second merchant U-boat disappeared in the Atlantic Ocean en route to Baltimore. What caused its disappearance and its final resting place are still unknown. In October the same year, U-53 surfaced at U.S. Naval Station Newport, in Newport, Rhode Island. While docked, the crew of U-53 offered the American sailors tours of the submarine. They also surfaced at the Station in an effort to show the United States their U-boats could access and operate off the east coast.

The Imperial Navy’s unrelenting aggression toward merchant vessels heading across the Atlantic to Great Britain finally turned the popular American opinion against Germany. In February 1917, Congress passed a $250-million arms appropriation bill. In March, German U-boats sank four more American merchant vessels, and on April 6, 1917, the United States declared war on Germany.

In 1918, two U-boats patrolled the east coast of the United States, torpedoing and firing 6” guns at American vessels. U-140 sank seven vessels off the east coast between July 2 and September 20, 1918. On August 4, U-140 was off Virginia’s coast, and sank one vessel. U-140 approached the northern-most part of the Cape Hatteras Nation Seashore on August 5, then next headed south along the Outer Banks. In the following days U-140 came across two vessels in close vicinity of one another. The first, a steamer, SS Merak, hauling a cargo of fruit, spotted the U-boat after being fired upon, and changed direction to prevent further attack. This vessel ran aground, so the crew abandoned ship. U-140 fired more torpedoes and sank SS Merak. Next, U-140’s focus shifted to another vessel. Light-vessel Diamond Shoal, which was operated by the U.S. Coast Guard, approached the area and witnessed the destruction of SS Merak. Radio operators on Diamond Shoal began sending out distress signals, alerting other ships of U-140’s presence and location. The Light-vessel was ultimately sunk by multiple torpedo strikes and gunfire, yet every member of the crew was able to abandon ship and make it to the shore unharmed. These incidents happened close enough to shore that residents on Hatteras Island reported being able to hear the shots being fired.

U-117 was also patrolling the east coast during this time. Starting on July 11, 1918 and lasting until September 22 of the same year, U-117 sank 20 vessels, eight of which were small fishing boats. The U-boat damaged another three vessels and a warship.

On August 16, 1918, British tanker SS Mirlo was torpedoed by U-117 off the North Carolina coast. Spotting the U-boat and knowing an attack was imminent, the crew abandoned ship. Within ten minutes, since it was loaded with gasoline and oil, the tanker exploded. What happened next is known as one of the most, if not the most, heroic rescues in shipping history. The torpedo attack happened seven miles offshore, almost directly opposite of the Chicamacomico Life Saving Station, where a crew was on alert. Great amounts of oil and gasoline poured from the tanker, burning as it floated on the water. As they approached the wreckage the life saving crew, led by Captain John Allen Midgette, was met by a wall of fire and smoke. The heat from the highly explosive fluids was so intense that it caused the lifesavers’ hair to singe, the cork life-vests to smoke, and the paint on the rescue boat to blister and melt. The flames were reportedly hundreds of feet high, but despite the extreme obstacles, the lifesaving crew was able to rescue 42 of the 51 British sailors from the water. The nine sailors who perished drowned when their lifeboat capsized. Following the valiant, almost seven-hour rescue mission, a local newspaper printed an article with the headline reading, “Ocean Catches On Fire.” In the Station log, Captain John Allen Midgette wrote, “Returned to Station at 11:00PM. Myself and crew very tired.”

U-117, like other U-boats, was also responsible for setting mines in the water. On August 29, 1918, American warship USS Minnesota sustained damage from coming in contact with a mine off Delaware’s coast. U-117 is believed to have placed the mine, which caused substantial damage to the destroyer. No one on the ship was killed so, despite sustaining serious damages, USS Minnesota reached Philadelphia where she underwent five months of repairs.

A few months later, on November 11, 1918, the Armistice was signed, ending hostilities on the Western Front. The Treaty of Versailles, signed on June 28, 1919 officially ending the war, demanded Germany accepted responsibility for starting World War One. The Treaty also placed restrictions on how many people could be in the German army, and prevented Germany from possessing tanks, warships, and submarines. The tanks, warships, and submarines were given to the Allied Powers as “prizes”. U-140 and U-117 – the same two submarines that had patrolled the coast off North Carolina – were given to the United States, along with four others. In February of 1919 the U.S. Navy acquired U-140 for testing. U-117, taken over by the U.S. Navy in November 1918, was also used for the same purpose.

The United States Navy used destroyers to test and practice war techniques in an effort to learn more effective ways to sink enemy vessels. Other testing was completed by bombing the U-boats from airplanes, something advocated for by William “Billy” Mitchell. Mitchell believed aerial attacks to be the most efficient way to combat enemy ships and submarines, and tried to convince the U.S. military of this throughout his entire career. He dropped bombs on the U-boats, simulating an aerial assault, and proved his theory to be accurate. A destroyer ultimately sank U-140 on July 22, 1919. U-117 was sunk on June 21, 1921, due, in part, to air attacks. Both U-boats were sunk off the Virginia coast.

A “Thank You” is due to Mr. Michael Lowrey for his presentation about U-boats off the North Carolina coast during World War One. For detailed descriptions about U-boats and other vessels used during World War One and World War Two, go to uboats.net.

Also, the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. has a great exhibit on World War I, which includes a display about Billy Mitchell.