A First-Timer's Trip to Portsmouth

Over the past four years that I've lived on Ocracoke, events – some planned, some not – motivated me to explore and learn more about the island, many times through listening to locals tell stories and reading about local history. Other times it’s been done through walking my dogs and observing and listening to my surroundings.

South Point and the route to it from ORV Ramp 72 is one of those walks, and if you go all the way, as far as you can go, you’ll see Ocracoke Inlet. Inlets are neat all on their own, but across the Ocracoke Inlet, where the Atlantic Ocean and Pamlico Sound meet, sits Portsmouth Island, once home to a flourishing shipping-turned-fishing village.

Portsmouth Island is the northern-most part of the Cape Lookout National Seashore and, similarly to Ocracoke (I say “similarly” because there is an airport here), is only accessible by boat. If you go to the right, beyond where vehicles are permitted at South Point, you can see Ocracoke Village to your front-right and a few buildings of Portsmouth Village to your front-left. The steeple of Portsmouth’s United Methodist Church can be seen above the old cedar and juniper trees, and you can also faintly spot the Henry Pigott house, sitting very near the Pamlico Sound. I became more and more curious about (maybe even slightly obsessed with?) the remote island and uninhabited village every time I walked to South Point. By sheer luck, local Amy Howard came into Ocracoke’s Visitor Center, where I work, the weekend before New Year’s Eve. She mentioned an excursion to Portsmouth was being planned, and I went into full-on “OMG!” mode, expressing my desire to join the group.

On New Year’s Eve a group of ten of people met at what is known, according to local historian Philip Howard (Amy’s father), as “Jack Willis’” dock, which is located next to Ocracoke’s Working Watermen’s Exhibit (in the former “Jack’s Store”) in the Community Square. Captain Donald Austin, of the Austin Boat Tours who frequently take people to Portsmouth, had us loaded in the skiff and ready to go by 10 o’clock. On the trip over, Captain Austin slowed the boat a few times, offering neat tidbits of Ocracoke and Portsmouth history. Austin speaks with the distinctive Ocracoke Brogue, which added even more charm to the trip. Once we had cleared Silver Lake Harbor, Donald sped up the boat. I thought it’d be brilliant to sit at the front of the skiff because I wanted a good view. The view was great from where I was sitting for sure, but I quickly learned that spot was prime Sound-spray seating, but not because of any fault of the Captain. The next time he slowed us down, I promptly put on my waterproof jacket. Lesson learned.

After about 20 minutes we arrived at the National Park Service docks at Portsmouth, and immediately noticed bunches of seashells that had been broken. Gulls have figured out that dropping clams onto a hard surface will break the shells, thus making mealtime a bit easier (the same thing can be seen on the roads, too). I’d never seen so many at eye-level, so I was absolutely tickled (it’s okay to call me a Northern Dingbatter because of my reaction). The dock, Philip Howard explained, was designed with gaps along the low side rails so the shells can be easily swept off the sides into the water.

Upon arriving at Portsmouth – after noticing the large amount of busted clamshells on the dock – you’ll realize there is a complete lack of usual sounds. No vehicle engines or horns, no barking dogs, no home heating/cooling unit fans spinning, no music, no man-made machinery. Even cell phones were quiet. You will, however, see salt marsh and water, cedar and juniper trees, hear bird chirps, and recognize the faint sound of tall grasses being moved by the wind. Since there are no paved roads or walkways, the dirt walkways-turned-mud (due to rain) will squish-squash under your feet. When combined with the aforementioned observations, you will realize that you are truly in a secluded, remote location.

One aspect of Portsmouth Island that we thankfully did not experience was the insects. Mosquitoes and greenhead horseflies are said to be brutal during the warm months, forcing people to wear mosquito netting or just hoping for the best. Park Service volunteers can stay in the village during the warm months, and are responsible for cleaning the buildings, mowing the grass, and opening the homes for visitors. The volunteer housing, marked as the “Summer Kitchen,” is directly in front of the United States Life Saving Station. A couple who were on this trip had stayed on Portsmouth for about six weeks, and after four years returned to the island. They said the mosquitoes could be dealt with; it was the greenhead horseflies that were horrible. But they also spoke about how unique of an experience it was to stay in the village. Both enjoyed doing their volunteer duties during the day, but they both expressed how nice it was to have an entire village to themselves in the evenings.

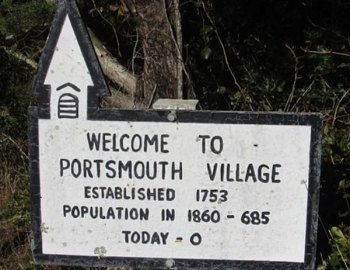

Our first stop was at the Theodore and Anne Salter House (built circa 1905), where a fantastic exhibit is located. Inside, visitors can read about Portsmouth’s history, and gather brochures and maps. There is also a “cancellation station” for those who carry National Park Service Passports, as well as paper for those who don’t have the Passport but want a stamp. One exhibit that caught my attention was about “Lightering.” When large ships carrying cargo couldn’t pass over shoals or navigate the channels, cargo was loaded onto smaller boats until the large ship was able to cross or until the goods needed to be moved. Portsmouth Village was established in 1753, and within 20 years was a thriving “lightering” village, providing warehouses and docks that enabled goods to be stored and then passed through the inlet.

In 1860 the population of Portsmouth village was 685, but when the Union Army made its way down to the Outer Banks in the first years of the American Civil War, many of Portsmouth’s residents moved to the mainland and never returned. The population decreased, and with “lightering” and shipping no longer being viable ways to earn money in the years after the Civil War, the villagers turned to fishing as their primary occupation.

After we got ourselves situated and oriented, our guide, Philip Howard, next took us to the Post Office. The Post Office was used more for than sending and receiving mail; it served as a general store, selling goods to the residents that the island could not provide. The rectangular building was constructed around 1900, and became a gathering place when residents came to pick up their mail. Inside, one long counter was designed for mail drop-off and delivery, with one half being set up with food cases and displays. Behind the counter were shelves where canned goods were stored, and on the other side there was a small amount of room for people to mingle. This same space is where you can see the mail cart. Alfred Dixon, and later on his son Carl, brought the mail from Ocracoke and Morehead City by boat, then loaded it into a wheelbarrow and rolled the deliveries to the Post Office.

Following our visit to the Post Office, we took the muddy, puddle-filled road to the one-room schoolhouse. As we approached the schoolhouse, we passed the Cecil and Leona Gilgo House (circa 1905) on our left. Philip told us his grandfather was stationed on Portsmouth Island with the United States Coast Guard from 1913-1917. Philip’s father, Lawton Howard (born in 1911), had memories of being on Portsmouth near the Cecil and Leona Gilgo House as a young child.

The schoolhouse is a small building, housing about nine student desks and one teacher desk. The blackboard stretched almost the entire length of the wall behind the teacher’s desk, and atlases of the world’s continents were displayed throughout the school. Also on display are student lists and photographs. The backside of the school faces the road, so you have to walk around the building to access the front door. Just beyond the schoolhouse and schoolyard is a trail. The half-mile trail will take you to a now-open field where the Maritime Hospital, a facility with personnel to treat sick and injured captains and sailors, once stood. All that is left of the hospital is a cistern.

After exploring the schoolhouse, we retraced our steps and made our way toward the Henry Pigott House. The Theodore and Anne Salter House was seen to our left, along with the Walker and Sarah Styron House (circa 1850), as we meandered down the road. The Henry Pigott House, which can be seen from Ocracoke’s southern end, sits next to a canal, with the Pamlico Sound to the rear. The yellow home with white trim is surrounded by a white-picket fence, has a sizeable shed, and a double-seater outhouse (other homes may have also had double-seater outhouses, but the one at this home was able to be opened). Henry Pigott was the last male resident of the village. As Henry’s health declined, Captain Donald Austin told us (on our return trip to Ocracoke) his family cared for Pigott, which Donald remembers. Henry Pigott died in 1971.

We back-peddled again and made our way toward the United Methodist Church. Once we passed the Post Office (on our right), the road curved slightly to the left. Two small wooden bridges led us to the church. On our right stood the George and Patsy Dixon House, built circa 1875. The home had an attached kitchen, but it was blown off due to a cyclone. When approaching the house from the Post Office, it looks as if it’s floating in the marsh (it did to me anyway), but once you continue toward the building it’s evident the house sits on dry land, with the marsh to its right.

The current Portsmouth United Methodist Church was built around 1914 and sits in an open, grassy area. The Pamlico Sound and salt marsh can be seen in the background, with the Henry Pigott House to the distant rear-left. The first church built in Portsmouth Village was destroyed in the storm of 1899. A second church was then erected, but was destroyed by the 1913 storm. Money to rebuild the church the third time was collected by Keeper Charlie McWilliams of the United States Life Saving Station on Portsmouth. In 1956 services at the church were discontinued. The church’s steeple can be spotted from the southern end of Ocracoke.

When we arrived at the Church, the sun was beginning to warm the air and the clouds were breaking up, making the walking tour even more enjoyable. The front door of the church has been boarded shut and wooden beams have been placed at the front sides of the building for support. Hurricane Sandy, which battered the East Coast in 2012, caused damage to the church, forcing the National Park Service to close the building to the public and put the wooden beams in place. Except for part of the steeple and its over-hanging sun-and-salt faded green eves, the long, rectangular church is white. The window glass, like the other buildings in the village, appears wavy, indicating it was made long ago.

After seeing the church I ventured off on my own for a bit, walking in the area behind the building toward the water. I saw some still-standing homes and discovered remnants of residences that once stood. Blocks of wood used to keep homes off the low-lying ground and crumbled chimneys were all that was left. I also saw a small fenced in cemetery behind the church, where Henry Pigott is buried. Beyond the homes is an open space, which leads to the salt marsh. From this vantage point you can look out over the Pamlico Sound and see the brilliant white tower of the Ocracoke Lighthouse off in the distance.

….. to be continued. Stay tuned for Part II of Crystal's visit to Portsmouth!