Shipwreck Beams Exposed By Gale

Over the years toredo worms and violent storms have reduced most of these ships to fragments which alternate between burial and disinterment in the surf zone.

Apparently last week’s gale exposed an impressive piece of what had to have been an old sailing ship north of ramp 67. It came to my attention when Ocracoke resident Rob King posted some impressive photos on Facebook. The dog needed to walk and so did the editor so I took them both up there the other afternoon to have a look.

We arrived at the site when the tide was up from when Rob had photographed the wreck so it was slightly awash but we could clearly see it was a substantially-built section of a ship’s hull with thick outer planks, closely spaced frames (or ribs), and equally thick ceilings (inner planks to protect the hull planks from the cargo as well as to provide extra longitudinal strength). A few yards inland of the section was a separate plank which was high and dry enough to allow a more thorough inspection.

The first thing that caught my eye was a well-preserved trunnel (wooden peg used long ago to fasten ships’ planking) so I knew we were looking at an old vessel. But very close to the trunnel were a couple of very rusty iron spikes. I knew trunnels were used centuries before metal fastenings, not only on ships but on buildings ashore as well. I hadn’t been aware that they were used in conjunction until I did a little on-line research. Evidently iron fastenings were introduced gradually in the 18thcentury but were used sparingly along with a larger number of locust trunnels. According to one source, the iron fastenings were vastly outnumbered by trunnels until around 1870 when wood and iron were used in more or less equal portions.

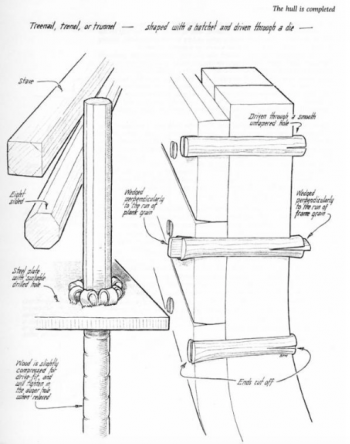

I found the following diagram and explanation online, which I’m throwing in to help clarify what we’re talking about.

Treenails were used as fasteners for shipbuilding. They were often made of locust wood. They were less expensive than bolts for fastening, and they made tight connections. The treenail is like a large dowel, pounded into a hole drilled through the pieces of wood to be fastened together, and set by pounding wedges into both ends, so that the treenail will not come out. Treenails were often called "trunnels."

This image is from Basil Greenhill and Sam Manning, The Evolution of the Wooden Ship, 1988, p. 145. Used by permission of the artist, Sam Manning.

Having left our car on the shoulder of highway 12 at the entrance to ramp 67, we walked for a good 30 minutes before reaching the wreckage so we knew it was at least a mile north of the ramp. I suspected the fragments were part of one of several Ocracoke shipwrecks noted in Kevin Duffus’s book Shipwrecks of the Outer Banks so after we got back I tried to look it up there. The only wreck that was close was the three-masted schooner Nomis, which grounded on August 16, 1935 and was photographed by one of the teachers from Ocracoke School. Duffus located the wreck .4 miles NE of ramp 67 at latitude 35-08-00 N, longitude 75-54-00 W.

The next day we went back, this time with my hand-held Garmin GPS, and decided to approach from the Pony Pens walkover, thinking it must be closer. A lengthy stroll to the southwest convinced us it was close to midway between the Pony Pens and ramp 67. The GPS put the wreck at 35-08-368 N, 75-53-202 W. A big green mile post sign on the beach showed it to be a quarter of a mile SW of Mile Post 80.

Even within the two-day period between our visits, the planks were visibly being reclaimed by the sand. The ceilings (inner planks) were already submerged out of sight. Who knows? In a matter of weeks it may be completely covered, awaiting the next storm to help it reappear.

Of course we have no real way of knowing if this is indeed part of the Nomis. But if it is, the sight is not as forlorn as it might otherwise have been. All six people aboard the Nomis were rescued and her cargo, 338,000 board feet of lumber, was salvaged and put to good use. Few of the other occupants of the “graveyard” were as lucky!