When I recently went back to Ocracoke's Loop Shack Hill (the site of a U-boat monitoring system during WWII) to take another round of photos, I left wanting to see photos of that area from WWII. I went to the Ocracoke Preservation Society Museum (OPS) in search of the photos, but left with far more.

When I spoke with OPS employees Rachel and Andrea, they welcomed me to explore the binders and plastic covers containing images and documents from the United States Navy base that was built in the village in 1942. There were documents, transmission records, and photographs from 1942 through the time when the Navy Beach Jumpers arrived on the island. What I found was fascinating.

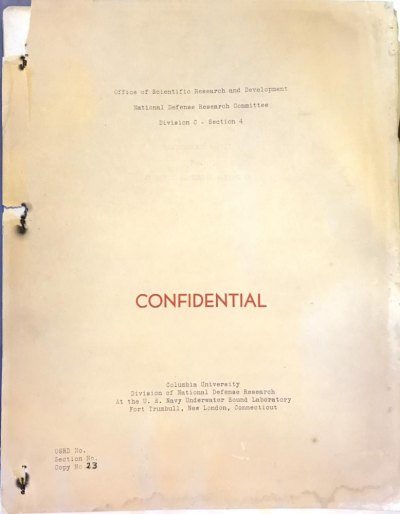

One of the first documents Rachel handed to me was a training manual which read, in bright red letters, “Confidential.” Of course it’s now declassified, though I don’t know when that happened, but it was still neat to hold something that at one point was secret. It’s not every day a regular civilian such as myself (regular citizen as opposed to someone who works in intelligence) gets to hold an original “Confidential” document. Many of the intelligence collection agencies we hear a lot about today weren’t established until after World War II ended, so it crossed my mind that I was possibly holding something that even some of the most brilliant minds in America hadn’t held.

I’d ask a member of the intelligence community if my thought was valid or just the daydream of 30-something woman with an imagination run wild, but I’d probably get, “No comment,” as the answer (you know how spies are *eye roll*), and, quite honestly, do I really need someone to burst my bubble? No, no I do not.

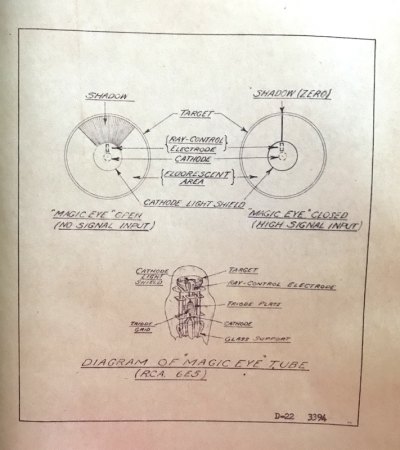

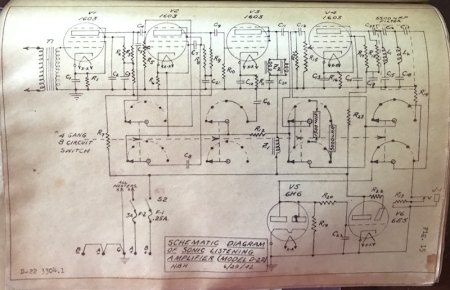

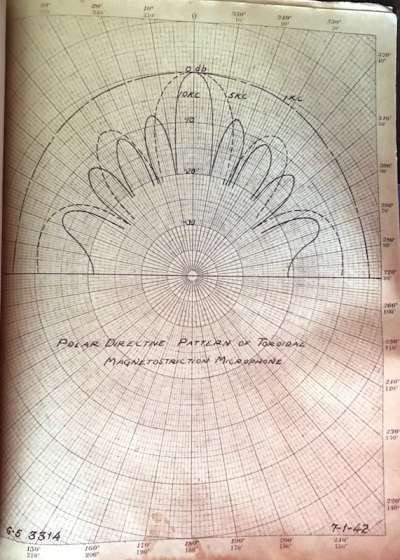

Anyway, so this confidential training manual was used to teach Navy personnel how to operate sonar listening devices which were used to track allied and enemy vessels that were traveling just off the coast. The men were trained at the Navy base in Ocracoke village, and a lot happened before and while those men were here.

Some of the most interesting information I found at OPS comes from Ocracoke native and historian Ellen Cloud. When she worked at OPS she compiled a wonderful binder that details, through documents, photographs, and eye-witness accounts, what happened on Ocracoke during the war.

The first documents that struck me while looking through her binder were written correspondences between Cloud and the National Archives. While at OPS, Cloud received a grant to research Ocracoke’s WWII history, so she dove into collecting information about the Navy base. Communicating with the National Archives may not seem that interesting, but what is exceedingly interesting is what the National Archives sent in response to her written requests for information. Below are portions of the letters she received.

In a letter dated December 13, 1993, William F. Sherman of the Civil Office Branch responded to Cloud’s letter writing:

We do not have records of maritime protests, or of entrances and clearances of vessel from Ocracoke.

I have referred a copy of your letter to our Military Reference Branch for information on World War II naval facilities on Ocracoke Island.

The next letter was dated December 21, 1993. Richard A. von Doenhoff wrote:

We are not aware of any U.S. Navy facilities on Ocracoke Island during World War II. The U.S. Coast Guard maintained facilities on that island, and they came under the operational control of the Navy Department during the war. However, the Coast Guard records pertaining to their shore facilities are in the custody of the Civil Reference Branch.

In the letter, von Doenhoff encouraged Cloud to write to the National Archives – Mid Atlantic Region for information that may be in the records of the Fifth Naval District (Group 181).

The final letter to Cloud was sent from a representative from the Cartographic and Architectural Branch of the National Archives. This letter was dated January 31, 1994.

We have checked our finding aids for Record Group 181, Records of Naval Districts and Shore Establishments, and have been unable to locate any references to Ocracoke Island or a naval facility located there.

After reading the letters I was left wondering how in the world the base’s existence could not be documented anywhere. There are photographs, documents, and personal accounts of what happened here, yet the federal government either doesn’t have the records, is unwilling to share those records, or has “accidentally” misplaced the records. I have yet to be able to determine which of those is most likely to be the case, but I have sent in a request to the National Archives to access information about military activity on Ocracoke Island during WWII. The N.C. State Archives has an entry by Ocracoke historian Earl O'Neal, but the feds know nothing. For now let’s focus on what we do have, not on what we don’t.

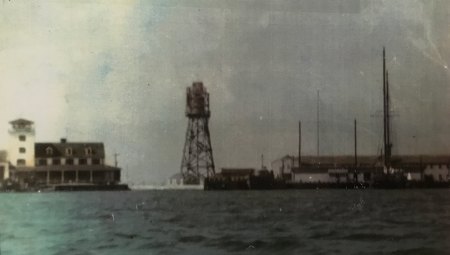

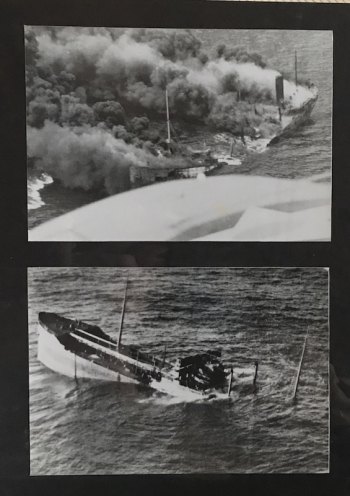

In 1883, the United States Life Saving Service (U.S.L.S.S.) built a station on Ocracoke’s north end at Hatteras Inlet approximately in the location where the ferry terminal is today. In 1904, the U.S.L.S.S built a station in Ocracoke Village, and in 1939 – the same year World War II began – the United States Coast Guard (U.S.C.G.) replaced that facility with a new station. That same year Silver Lake was dredged for the first time and in 1940 station construction was completed. Almost immediately after WWII began, German u-boats began patrolling the east Coast of the United States, sinking merchant and allied vessels. The beams of light from the lighthouses and the light used in residences along the Outer Banks made locating ships even easier for the Germans, and in the first month of the war (September 1939) twelve vessels were sunk, followed by over 50 sinkings in the next three months. Despite the enemy being so close to our shores and knowing friendly vessels were being sunk, the United States remained uninvolved in combat.

That changed in December of 1941 when Japanese forces attacked the U.S. Navy base located at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Up until the attack, only 8% of Americans were interested in fighting another war. After Pearl Harbor, the United States was thrust into the war in the Pacific and in the days following the attack, Germany declared war on the U.S. The Japanese decimated our naval capabilities, leaving the country unprepared and unable to protect itself against the German u-boat threat. To help combat who was now a common enemy, Great Britain sent 24 Royal Navy Patrol Service (R.N.P.S.) trawlers equipped with anti-aircraft and anti-submarine weaponry to help defend the U.S. East Coast. These converted fishing vessels began arriving on the East Coast of the U.S. in March of 1942.

In late-April 1942, the Department of the Navy ordered a base be built in Buxton, on Hatteras Island, in an effort to protect allied vessels from u-boat attacks (the 12 buildings that comprised the navy base were destroyed prior to 2013 by the U.S.C.G. and the property handed over to the National Park Service).

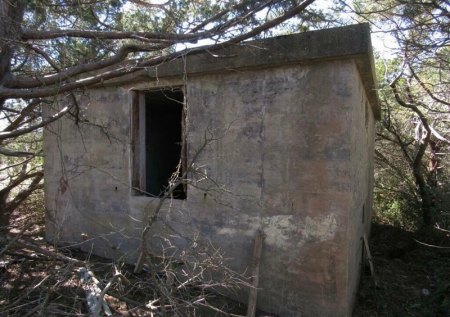

Beginning in May and lasting through June 1942, the United States Navy base on Ocracoke was built to coincide with Hatteras Minefield Patrol operations. The largest part of the base was built where the NPS visitor center and Mainland ferry terminals are today. A smaller naval operation was established in an area locals once called Bald Beach. Once the Navy established this area as a communications facility it became known as Loop Shack Hill.

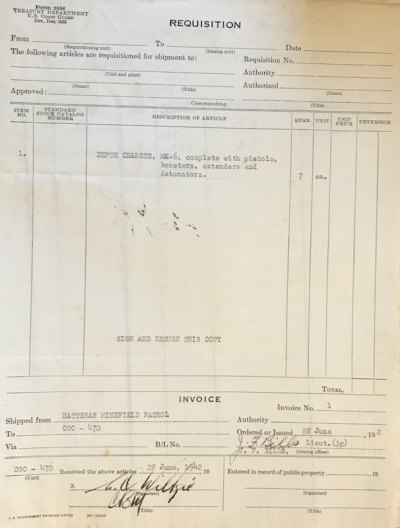

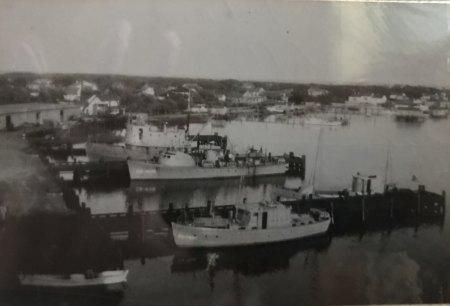

Silver Lake was once again dredged, allowing room for three 135-foot piers and 12 vessels to dock. The piers were built where the NPS public boats docks are currently. The base was also used as a refueling station. The 12 vessels stationed at Ocracoke were used for patrolling the waters off the coast, aiding in the protection of shipping vessels, and for going on search and rescue missions. These and other vessels placed 2,635 mines to protect and monitor the waters from Buxton down through the Ocracoke Navy base. These mines were monitored, replaced, and set-up by the Hatteras Minefield Patrol. According to documents provided by OPS, the crews who worked the minefield were made up of men from the Hatteras and Ocracoke navy bases.

The Navy also installed a magnetic wire along the same route to monitor underwater activity off the coast and signals were sent to Loop Shack Hill. Here, through a sonar communications tower, Navy personnel monitored submarine activity with the devices they’d learned to use in the Confidential manual I mentioned earlier. Radar and advanced communications capabilities were also installed at Loop Shack Hill. Radar allowed Navy personnel to monitor U-boat activity;then they would use radio signals to jam signals going to and coming from u-boats when they surfaced. The advanced communications capabilities allowed sensitive information to be passed to and from Ocracoke Island.

Towards mid-May of 1942, the HMT Bedfordshire – a R.N.P.S. vessel sent to patrol the North Carolina coast –was sunk by a German u-boat off Cape Lookout. Several days later Jeffrey Garrish, who was monitoring sonar activity from Loop Shack Hill, found the body of Ordinary Telegraphist Stanley Craig in the surf near the communications facilities (keep in mind the landscape of Ocracoke looked completely different then compared to what it does now. Loop Shack Hill is almost directly across from the entrance to ORV Ramp 72, but during the war that area was almost completely flat with a straight-shot view of the Atlantic Ocean.) Resident Iona Teeter was told about the discovery of Craig’s body and had her father accompany her on a drive towards Ocracoke Inlet. As they reached the southern part of the island they found the body of Sub-lieutenant Thomas Cunningham.

Up until 1943, naval operations, which still included sonar, radar, and advanced communications capabilities, as well as minefield patrols and rescue missions, continued as they had been until the winter of 1943. The role of the base changed for the remainder of the war, but the base itself – how it was constructed and how it impacted the lifestyles of the residents – caused quite a bit of controversy and heartbreak for the islanders when it was built.

Stay tuned for the second part of this series which will detail island wartime life and how the role of the Navy base changed.