Ocracoke's Civil War monument briefly displayed a Confederate flag earlier this week.

The recent hate crime that occurred in a Charleston, South Carolina church has sparked an intense debate about what many people identify as the Confederate Flag. Supporters of the flag claim it is "Heritage, Not Hate," while its opponents demand it be removed from all state and federal buildings and property.

Ocracoke, while secluded, is not immune from acts that some people perceive as hateful or offensive. A major source tension along the Outer Banks stems from the restrictions and new requirements put in place and enforced by the National Park Service. The Audubon Society has also been on the receiving end of a lot of bitterness, and many folks have a bumper sticker depicting a middle finger bring raised that reads, "Hey Audubon, Identify this Bird."

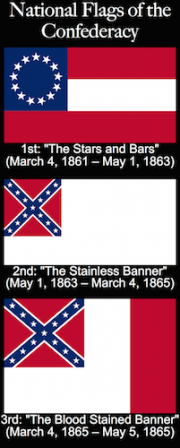

Recently, from my own observations, more and more people have been placing the Confederate flag (which is more accurately called the Battle Flag of the Army of Northern Virginia if it's square or the Southern Cross used by the Army of Tennessee if it's a rectangle) on their vehicles, have them displayed on the beach, have patches or designs on clothing, or hanging in various yards around the village. This flag isn't something new to this country, nor are the opinions of its supporters or opponents. Now its perceived meaning(s) (whether positive or negative, or their historical accuracy) have been thrust into the limelight and have sparked a national, sometimes bitter, debate. This week an unusual flag placement was seen on a historical monument. Here's a little background information.

Ocracoke has a fascinating history. Throughout the village you can see markers and memorials commemorating people and events, go on guided tours to learn the local lore, visit the museums, attend public talks presented by life-long residents and descendants of Ocracoke's original settlers, or read books, journals, and newsletters about the rich and sometimes tumultuous local documented history.

One such historical event has been remembered through a marker. Placed at the National Park Service public parking area, near the Visitor Center and Pamlico Sound, is a small Civil War monument. The black granite marker commemorates Fort Ocracoke, and both the Union and Confederate troops who served their countries here in the early months of the American Civil War. Usually, from what I can tell, people visit the marker to learn some more history. The marker, again as far as I can tell, has never been a source of anger or resentment, and serves to detail the brief but important skirmishes that occurred on Ocracoke during the Civil War.

Ocracoke Inlet was an important and bustling shipping channel since early colonial days, and Hatteras Inlet became just as important from the time it and Oregon Inlet were carved in 1846 by a massive, powerful hurricane.

When tensions between the States grew in the early 1860's (after Abraham Lincoln was elected President), Confederate soldiers began constructing forts along North Carolina's coast in an effort to protect these shipping channels from Union occupation. The first shots of the American Civil War were fired on April 12, 1861 at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, and on May 20, 1861, North Carolina seceded from the Union. The people who lived on the Outer Banks primarily remained neutral during the war and didn't consider themselves to be a part of the conflict.

The Outer Banks were invaded twice; once by Confederate troops and once by Union troops. When Confederate volunteers, known as the Washington Grays, invaded Portsmouth and Ocracoke, they did so because the Confederacy recognized the importance of the inlets. If these inlets were cut off by Federal troops, the Confederacy would lose vital shipping channels and would be left unable to send or receive necessary supplies and materials. Although North Carolina didn't secede until May 20, 1861, the Confederacy had already claimed Portsmouth and Ocracoke Island as its own. On May 20, 1861 (the day North Carolina seceded from the Union), more Washington Grays arrived on the islands, and construction of Fort Ocracoke – located on Beacon Island, northwest of Ocracoke Inlet, between Ocracoke and Portsmouth Island – began.

The fort was completed in about two weeks by enlisted men and African-American slaves, and in the following months more men from the mainland enlisted. They arrived to serve in Fort Ocracoke in an effort to protect the inlets and prevent Union troops from accessing New Bern, NC.

In August of 1861, the majority of Confederate troops located in Fort Ocracoke were moved to Fort Hatteras, which was on Hatteras Island. The remaining troops in Fort Ocracoke weren't many. The Union army successfully overtook Fort Hatteras and captured the Confederate troops within. Upon hearing this news, the men who had stayed behind in Fort Ocracoke abandoned the site. Some of those men destroyed weapons and supplies, then removed and took the flag before embarking on toward New Bern, NC.

Portsmouth Island was nearly abandoned as well. Soldiers and residents both left the island and headed for safety on the mainland. In September of 1861, Federal troops arrived and destroyed abandoned Confederate sites on Portsmouth Island and the entirety of Fort Ocracoke. The Union army is credited with causing the only destruction on Ocracoke. Two schools and some homes were burned, but no lives were lost here during these early months of the war. Before leaving the area, Federal troops sank two vessels to block Ocracoke Inlet from being used by Confederate ships.

Men from both Ocracoke and Portsmouth enlisted, and it is believed the majority joined the Federal forces, though some did join the Confederate Army. Coastal counties were under Union control by mid-1862, with their headquarters in New Bern.

The Civil War events on the Outer Banks were limited, and while those conflicts weren't on the same scale as Gettysburg or other large battles, it's still important to know what happened. It's also important that we respect each other, monuments, and public property.

I spoke to several visitors on the day the Confederate flag appeared at the Civil War marker on Ocracoke. One man spoke out and said it was upsetting to approach the monument with his bi-racial grand children, only to see the flag, which he feels is a symbol of hate and intolerance. A woman in her early 30's who described herself as a conservative in every way, said she didn't think flying that flag was wrong, unless it is placed on state or federal property. Another woman said she is sick over all the disagreements over the flags and feels it just needs to be left alone unless, again, it's on public property. Two other people said that no matter what, since it offends an entire race of people, it's inappropriate. The flag debate will probably continue to intensify, and the people who believe it's "Heritage, Not Hate" will continue to fly the flags, just as the people who oppose it will continue to work to have it removed from state and federal property.

The flag that was placed next to the Fort Ocracoke marker was removed sometime the same afternoon by an unknown person or persons.

Ocracoke typically brings a sense of relaxation, and can be enjoyed by everyone and anyone. There's a wonderful and unique history here that dates back to the island's first visitors, the Woccock, a tribe of Native Americans, who like many people since, came here to fish. John White, a European explorer, put Ocracoke on the map in 1585 after discovering the tiny island while on his adventures up and down the North Carolina coast, and small settlements were established and reported in the early 1600's.

During the early months of the 1700's the colonial government stepped in and made Ocracoke a pilot town, allowing fishermen, mariners, merchants, and pilots to form a permanent community. These residents helped merchant ships navigate the treacherous and dynamic water of Ocracoke Inlet and the surrounding areas. It is believed that once European settlers began building communities on the island, Woccocock gradually morphed into the current pronunciation and eventual spelling of Ocra-coke.

One of Ocracoke's more notorious visitors was Edward Teach, more commonly known as Blackbeard the Pirate, who set up camp in the area we all know as Springer's Point. Blackbeard hosted a pirate gathering on Ocracoke in the fall of 1718, and colonial business interests feared that the pirates would control Ocracoke Inlet. Lt. Robert Maynard of British Royal Navy was dispatched to confront Blackbeard, who was ultimately killed by Maynard in the Battle of Ocracoke on November 22, 1718.

Ocracoke gradually disappeared from the public eye after Blackbeard was killed, but both the communities of Ocracoke and neighboring Portsmouth Village were thriving. The two villages became highly regarded by merchant mariners and Ocracoke Inlet was used heavily.

In 1783 the "Treaty of Paris" was signed, officially marking the independence of the United States from Great Britain. Part of the Treaty stated that Britain would abandon forts along the coast; however, these posts remained occupied by the British. As a result, the United States declared war on Great Britain, and on June 12, 1812, the War of 1812 began.

Throughout the war, Ocracoke Inlet remained very busy and the villages of Portsmouth and Ocracoke flourished. Once war was declared, the British conducted surprise attacks in an attempt to invade the newly-formed United States, and in July of 1813, the Royal Navy was seen approaching Portsmouth and Ocracoke. Over the course of several days, the Royal Navy destroyed hundreds of livestock, then made their way into Pamlico Sound in an effort to reach New Bern. A full-scale invasion was prevented by the fast-acting crew of the United States Revenue Cutter Mercury, a ship used to police the inner waterways. The Mercury reached the town of New Bern in enough time to warn the people and ward off a British invasion and occupation.

After the War of 1812, Ocracoke Inlet remained a highly traveled and accessible channel for merchant sailors. In 1822, land was purchased to build a light station in Ocracoke village, and in 1823 the Ocracoke Lighthouse was erected. The lighthouse has been a source of light and guidance for mariners and a source of joy for visitors since. A powerful hurricane carved Hatteras and Oregon Inlets in 1846, and shipping routes gradually began to change. In the decades following the hurricane and construction of the Ocracoke Lighthouse, the American Civil War began. After brief skirmishes, Ocracoke continued growing as a maritime, piloting, and fishing village.

During both World War One and World War Two, German U-boats were dangerously close to Ocracoke, torpedoing merchant and military vessels indiscriminately. During WWII, twenty-four British Royal Navy anti-submarine vessels were sent to the United States to help protect the East Coast from U-boat attacks and a possible German invasion. The HMT Bedfordshire, which was stationed in Morehead City, was sunk by a U-boat in May of 1942 while on patrol. Three days after the vessel was sunk, four bodies of sailors from the HMT Bedfordshire washed onto Ocracoke and were buried in the village by residents.

After World War Two ended, Ocracoke could return to being a peaceful maritime village, remaining secluded and tucked away. When the National Park Service established Ocracoke and Hatteras Islands as the Cape Hatteras National Seashore, travelers began to explore the islands more and more. Advancements in the 1950's, such as a state-run ferry system and paved roads, allowed easier access to Ocracoke. In the late-1970's a new water system replaced cisterns and hand pumps, which brought more development to this remote island.

Which brings us to today, when over ¾ of a million visitors from all over the U.S. and the world ride the ferries to Ocracoke each year. We invite them all to enjoy the island’s natural beauty, explore the village, and learn a little about our history and culture as well.